What It Really Means to Move Left of ATO

Move beyond speed to redefine security, collaboration, and mission readiness in federal authorization.

There’s no shortage of frustration when it comes to the federal Authority to Operate (ATO) process. Delays can mean days, months, or sometimes years for some. And the cost of that delay is a blown budget, operational drag, and missed mission windows. It’s the slow bleed of time, money, and energy that never creates an improvement for the warfighter.

At this year’s Billington CyberSecurity Summit, the message was clear: moving left of ATO is about more than just speed. It’s about purpose and building security into the process so early and natively that the question stops being when a system can go live, but how we’ve kept it secure from the start.

The Cost of Standing Still

The ATO process, as it currently stands, is expensive. David Raley, Digital Program Manager at the Marine Corps Community Services, pointed out during his Billington panel that a single ATO can run a million dollars per workload per year. Multiply that across thousands of packages, and you get more than a backlog. Government teams are losing years of productivity just trying to prove they meet controls that don’t always reflect the reality of modern threats or cloud-native environments. We’re spending serious resources to prove security after the fact. And too often, those efforts yield little more than documentation.

What Moving Left Actually Looks Like

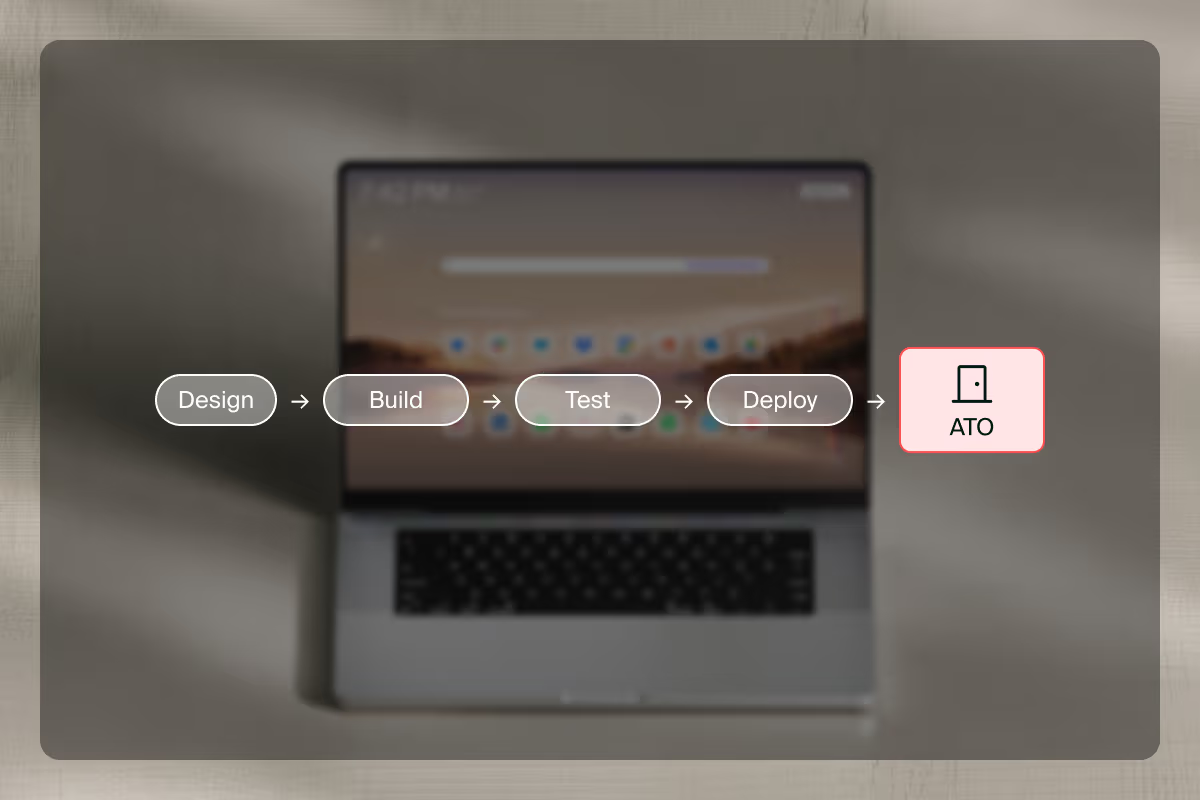

Moving left means moving beyond shifting timelines to changing who owns security and when. It’s about building pipelines that treat security as code. And most importantly, it’s about making sure those pipelines are actually usable by the people building the software.

When developers get real-time feedback on security issues, within the tools they already use, they can course-correct instantly. They don’t need to open a ticket or wait for an Information Security Officer (ISO) to weigh in weeks later. They see the issue, they fix it, and they move forward.

Some aspects of this process are already underway today. Operation StormBreaker, the only Marine Corps certified DevSecOps pipeline, for example, shared at Billington how they have cut the ATO timeline for containerized workloads from 18 months to 15 minutes in certain cases. That didn’t happen by accident. It required a rethink of how DevSecOps, compliance, and mission owners interact, with a shift toward automation and shared ownership of security from day one.

Just as important is to build it into the culture by talking about why improvement is so essential. DOD spent decades going slowly. Including everyone in the increase in pace culturally is critical to gaining acceptance.

Not Everything is High-Risk – and That’s the Point

There is a tendency in federal security to treat every control as if it’s mission-critical. However, the truth is that not all data holds the same value, and not all workloads carry the same level of risk.

That’s where automation shines. If you can tag workloads by risk tier and automate the review of low-risk, trivial controls, you free up time and energy to focus on what actually matters. You also reduce human error, increase consistency, and cut down on the subjectivity that tends to slow things down.

The idea of “shirt sizing” workloads – categorizing them by size and sensitivity – is a practical strategy for targeting effort where it counts and ignoring what doesn’t. It’s how you start to shrink the backlog and chip away at the wasted time and cost that bog down the ATO pipeline.

To get there, developers, assessors, security leads, and program owners need to work from the same information. That means democratizing access to security telemetry, automating artifact generation, and using standardized pipelines. When everyone is aligned on the same controls, formats, and data, approvals happen faster and we’re able to get capability to warfighters faster. The process change and approval should be fast because what happens to warfighters matters – and the delays are bureaucratic and procedural, not mission-oriented.

Vendors As Helpers, Not Gatekeepers

Another recurring theme at Billington was the role of industry in supporting this shift. Put simply, the government needs the right tools, not necessarily more of them. It needs partners who understand where and how their technology fits into the ATO process.

If a product can’t support infrastructure as code or integrate into CI/CD pipelines, it adds needless delay and friction. As vendors, we have a choice. We can be gatekeepers or we can be guides. We can show programs how to automate the right parts of compliance, inherit controls intelligently from cloud providers, and shift verification into the build process where it belongs.

Left of ATO is Not Just About Authorization

If there’s one key takeaway from the Billington panel, it’s that getting left of ATO is about faster feedback, inclusive culture, and teams that are aligned on mission.

Keeping everyone aligned on increasing warfighter effectiveness and mission success will drive the outcome that the left of ATO intends.

.svg)

.png)

.svg)

.svg)